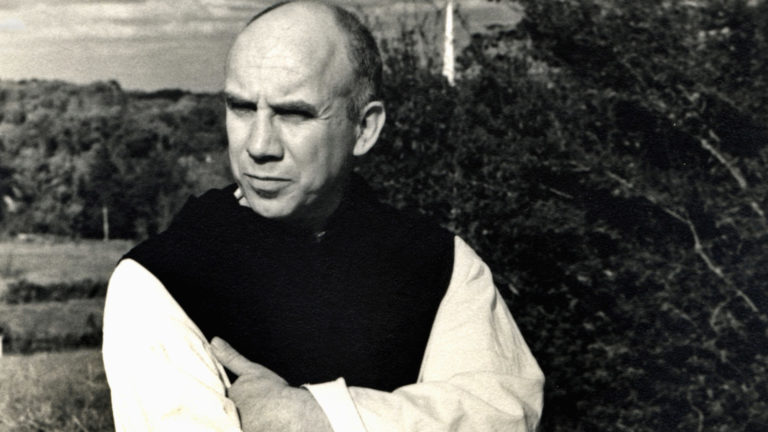

By Thomas Merton

By Thomas Merton

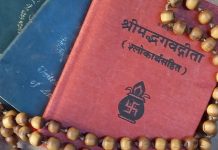

The word gita means “song.” Just as in the Bible the Song of Solomon has traditionally been known as “The Song of Songs” because it was interpreted to symbolize the ultimate union of Israel with God (in terms of human married love), so the Bhagavad-gita is, for Hinduism, the great and unsurpassed song that finds the secret of human life in the unquestioning surrender to and awareness of Krishna.

While the Vedas provide Hinduism with its basic ideas of cult and sacrifice and the Upanisads develop its metaphysic of contemplation; the Bhagavad-gita can be seen as the great treatise on the “active life.” But it is really something more, for it tends to fuse worship, action and contemplation in a fulfillment of daily duty that transcends all three by virtue of a higher consciousness: a consciousness of acting passively, of being an obedient instrument of a transcendent will. The Vedas, the Upanisads, and the Gita can be seen as the main literary supports for the great religious civilization of India, the oldest surviving culture in the world. The fact that the gita remains utterly vital today can be judged by the way such great reformers as Mohandas Gandhi and Vinoba Bhave both spontaneously based their lives and actions on it, and indeed commented on it in detail for their disciples. The present translation and commentary is another manifestation of the permanent living importance of the gita. Swami Bhaktivedanta brings to the West a salutary reminder that our highly activistic and one-sided culture is faced with a crisis that may end in self-destruction because it lacks the inner depth of an authentic metaphysical consciousness. Without such depth, our moral and political protestations are just so much verbiage. If, in the West, God can no longer be experienced as other than “dead,” it is because of an inner split and self-alienation that have characterized the Western mind in its single-minded dedication to only half of life: that which is exterior, objective, and quantitative. The “death of God” and the consequent death of genuine moral sense, respect for life, for humanity, for value, has expressed the death of an inner subjective quality of life: a quality that in the traditional religions was experienced in terms of God-consciousness. Not concentration on an idea or concept of God, still less on an image of God, but a sense of presence, of an ultimate ground of reality and meaning, from which life and love could spontaneously flower.

Realization of the Supreme “Player” whose “Play” (lila) is manifested in the million-formed, inexhaustible richness of beings and events, is what gives us the key to the meaning of life. Once we live in awareness of the cosmic dance and move in time with the Dancer, our life attains its true dimension. It is at once more serious and less serious than the life of one who does not sense this inner cosmic dynamism. To live without this illuminated consciousness is to live as a beast of burden, carrying one’s life with tragic seriousness as a huge, incomprehensible weight (see Camus’ interpretation of the Myth of Sisyphus). The weight of the burden is the seriousness with which one takes one’s own individual and separate self. To live with the true consciousness of life centered in Another is to lose one’s self-important seriousness and thus to live life as “play” in union with a Cosmic Player. It is he alone that one takes seriously. But to take him seriously is to find joy and spontaneity in everything, for everything is gift and grace. In other words, to live selfishly is to bear life as an intolerable burden. To live selflessly is to live in joy, realizing by experience that life itself is love and gift. To be a lover and a giver is to be a channel through which the Supreme Giver manifests his love in the world.

But the Gita presents a problem to some who read it in the present context of violence and war, which mark the crisis of the West. The Gita appears to accept and to justify war. Arjuna is exhorted to submit his will to Krishna by going to war against his enemies, who are also his own kin, because war is his duty as a prince and warrior. Here we are uneasily reminded of the fact that in Hinduism as well as in Judaism, Islam, and Christianity, there is a concept of a “Holy War” that is “willed by God,” and we are furthermore reminded of the fact that, historically, this concept has been secularized and inflated beyond measure. It has now “escalated” to the point where slaughter, violence, revolution, the annihilation of enemies, the extermination of entire populations and even genocide have become a way of life. There is hardly a nation on earth today that is not to some extent committed to a philosophy or to a mystique of violence. One way or other, whether on the left or on the right, whether in defense of a bloated establishment or of an improvised guerrilla government in the jungle, whether in terms of a police state or in terms of a ghetto revolution, the human race is polarizing itself into camps armed with everything from Molotov cocktails to the most sophisticated technological instruments of death. At such a time, the doctrine that “war is the will of God” can be disastrous if it is not handled with extreme care. For everyone seems in practice to be thinking along some such lines, with the exception of a few sensitive and well-meaning souls (mostly the kind of people who will read this book).

The Gita is not a justification of war, nor does it propound a war-making mystique. War is accepted in the context of a particular kind of ancient culture in which it could be and was subject to all kinds of limitations. (It is instructive to compare the severe religious limitations on war in the Christian Middle Ages with the subsequent development of war by nation-states in modern times-backed of course by the religious establishment.) Arjuna has an instinctive repugnance for war, and that is the chief reason why war is chosen as the example of the most repellent kind of duty. The Gita is saying that even in what appears to be most “unspiritual” one can act with pure intentions and thus be guided by Krishna consciousness. This consciousness itself will impose the most strict limitations on one’s use of violence because that use will not be directed by one’s own selfish interests, still less by cruelty, sadism, and mere blood lust.

The discoveries of Freud and others in modern times have, of course, alerted us to the fact that there are certain imperatives of culture and of conscience which appear pure on the surface and are in fact bestial in their roots. The greatest inhumanities have been perpetrated in the name of “humanity,” “civilization,” “progress,” “freedom,” “my country,” and of course “God.” This reminds us that in the cultivation of an inner spiritual consciousness there is a perpetual danger of self-deception, narcissism, self-righteous evasion of truth. In other words, the standard temptation of religious and spiritually minded people is to cultivate an inner sense of rightness or of peace and make this subjective feeling the final test of everything. As long as this feeling of rightness remains with them, they will do anything under the sun. But this inner feeling (as Auschwitz and the Eichmann case have shown) can coexist with the ultimate in human corruption.

The hazard of the spiritual quest is of course that its genuineness cannot be left to our own isolated subjective judgment alone. The fact that I am turned on doesn’t prove anything whatever. (Nor does the fact that I am turned off.) We do not simply create our own lives on our own terms. Any attempt to do so is ultimately an affirmation of our individual self as ultimate and supreme. This is a self-idolatry which is diametrically opposed to “Krishna consciousness” or to any other authentic form of religious or metaphysical consciousness.

The Gita sees that the basic problem of man is his endemic refusal to live by a will other than his own. For in striving to live entirely by his own individual will, instead of becoming free, man is enslaved by forces even more exterior and more delusory than his own transient fancies. He projects himself out of the present into the future. He tries to make for himself a future that accords with his own fantasy, and thereby escape from a present reality which he does not fully accept. And yet, when he moves into the future he wanted to create for himself, it becomes a present that is once again repugnant to him. And yet this is precisely what he has “made” for himself—t is his own karma. In accepting the present in all its reality as something to be dealt with precisely as it is, man comes to grips at once with his karma and with a providential will that, ultimately, is more his own than what he currently experiences, on a superficial level, as “his own will.” It is in surrendering a false and illusory liberty on the superficial level that man unites himself with the inner ground of reality and freedom in himself which is the will of God, of Krishna, of Providence, of Tao. These concepts do not all exactly coincide, but they have much in common. It is by remaining open to an infinite number of unexpected possibilities which transcend his own imagination and capacity to plan that man really fulfills his own need for freedom. The Gita, like the Gospels, teaches us to live in awareness of an inner truth that exceeds the grasp of our thought and cannot be subject to our own control. In following mere appetite for power, we are slaves of our own appetite. In obedience to that inner truth we are at last free.