By Abhishek Ghosh, Assistant Professor, Religious Studies and Liberal Studies, Grand Valley State University, originally published in Journal of Vaishnava Studies, Volume 25, Number 1 (Fall 2016), pp.251-252.

By Abhishek Ghosh, Assistant Professor, Religious Studies and Liberal Studies, Grand Valley State University, originally published in Journal of Vaishnava Studies, Volume 25, Number 1 (Fall 2016), pp.251-252.

Sacred Preface can be purchased here: http://darshanpress.com/shop/sacred-preface/

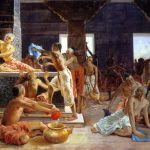

Swami B.V. Tripurari’s works are best located within a framework of Vaisnava-Hindu constructive theology written for a contemporary audience, and Sacred Preface is representative of such theologizing. His tradition – Caitanya or Gaudiya Vaisnavism – honors Krsnadasa Kaviraja’s early seventeenth-century text Sri Caitanya Caritamrta as a canon that blends together the founder Sri Caitanya’s (1486-1533) biography and theology. The invocatory verses of Sri Caitanya Caritamrta written in a series of Sanskrit verses (in an otherwise Bengali book), has the theological seeds that Krsnadasa helps blossom in the rest of the text. Swami Tripurari’s Sacred Preface adds a layer of English commentary to these prefatory verses of the Caitanya Caritamrta, with some of the original Sanskrit verses forming the backbone of the chapters of Swami’s book. Written by a dedicated practitioner from within the tradition, Sacred Preface reflects the insights of an authentic religious insider communicating many of the intricacies of his school’s doctrines to religious outsiders and insiders alike.

At the heart of this book is the methodology of Swami Tripurari’s constructive theologizing, which follows a hermeneutical trend set by Kedarnath Datta Bhaktivinoda (1838–1914), a predecessor theologian of the Vaisnava tradition. A century ago, Bhaktivinoda also commented on Caitanya Caritamrta and other canonical texts of his tradition, and a substantial part of Bhaktivinoda’s early works is geared toward engaging with post-Enlightenment rational ideas of a Western-educated Bengali intelligentsia. In a sense, the hermeneutical strategies Bhaktivinoda uses to examine the Bhagavata Purana in his 1896 work Krsna Samhita anticipate Swami’s Sacred Preface. Swami is well aware of this, and acknowledges that “Bhaktivinoda was the first in the Gaudiya lineage interpretive voice to interface Gaudiya Vedanta with modernity” and that he himself is a “child” of this lineage (xiv).

A key argument, surfacing repeatedly, suggests that transcendent reality is subjective, something attained through meditation, rather than objective, something that can be empirically defined in the material world. For instance, Swami is familiar with contemporary scholarship concerning the historiography of Krsna (35–36) but contends that the subjective reality of Krsna attained through meditation and experience is different from trying to objectivize Krsna as a historical figure. In a sense it parallels historian Ranajit Guha’s argument about Rabindranath Tagore and the Indian mode of remembering the past (itihasa) in his book History at the Limit of World History (Columbia, 2003). Swami seems to suggest that a Rankian historiography of Krsna is an attempt to locate the “supersubjective meditative reality within the objective material world . . . [but] texts such as the Bhagavata Purana are not objective history, psychology or science in any modern sense, even while they tell a sacred history, address yogic psychology, describe the methodology of science of spiritual practice, and describe the nature of consciousness and matter with an emphasis on the former” (36–37).

Such a hermeneutical stance opens up apparent conflict with literalist readings of the canonical texts of Caitanya Vaisnavism. Swami’s book might be as radical to his literalist readers as Bhaktivinoda’s Krsna Samhita was to his nineteenth-century contemporaries—but Swami’s “innovation” is not unprecedented within his own tradition.

Beyond its exegetical disposition, Sacred Preface is also significant in its engagement with contemporary intellectual discourses beyond the confines of Hindu or Vaisnava theology. Swami locates his discussion of Vaisnava doctrines within the broader discourse of Hindu theology, for instance, in his analysis of linear and cyclical time (93–95). However, in a manner reminiscent of Bhaktivinoda, throughout the book he engages deeply with relevant contemporary public and scholarly discourses in the realm of religion. We find in the pages of Sacred Preface a Vaisnava engagement with intellectuals ranging from Christian feminist theologians like Sallie McFague to New Athiests like Sam Harris. Peppered in the midst of this is a poetic invocation of Rudyard Kipling’s “If—” and references to peer-reviewed articles on quantum mechanics and consciousness studies. Engaging with such a broad range of ideas adds flavor to the central concerns of the book, as well depth to an understanding of Gaudiya theology.

Although Swami’s work is not, of course, academic, there are certain minor editorial details that would have added more polish to the book. For instance, while many works are cited in endnotes, for others no bibliographic information is available—N.S. Rajaram’s research discussed on page 36, for instance, or David Bentley Hart on page 54. In the bigger picture, however, Swami’s hermeneutical disposition makes the book very relevant for our times and demonstrates the intellectual innovations inherent in the Vaisnava tradition. Further, Swami’s prose has poetry embedded in it, and any aesthete would relish it as a doorway to the Caitanya Caritamrta, just as a native Bengali would experience the poetic aesthetics of the Caitanya Caritamrta in its original.

Sacred Preface. By Swami B.V. Tripurari. Palo Alto: Darshan Press, 2016. Pp. xx+237. $20.00 (hardbound with jacket)