by Swami B.V. Tripurari

Sri Rupa Goswami has described Sri Caitanyadeva as greatly munificent—maha vadanyaya. Similarly, throughout the considerable literature describing Sri Caitanya there is an emphasis on his compassionate nature, an emphasis that distinguishes him from other manifestations of the Godhead within Hinduism. In contrast, the God of the Gaudiya cannon—Bhagavan—is more typically noted for his impassibility, for his being incapable of feeling material suffering, which in turn brings his ability to empathize into question. (1)

The Godhead’s impassibility has much to do with why he is God and why he thus has the capacity to bring about salvation: He is not in need of being saved himself and is never touched by the deluding influence of his maya-sakti. Were he so influenced, his capacity to bestow salvation would be in question. At the same time, it is direct experience of the suffering of others that enables one to most readily empathize with them, to feel compassion for their plight. Thus the need to navigate the theological course between God’s impassibility and his compassion arises. How can he effectively remain impassible and at the same time be filled with compassion for the suffering animation?

While Krsna has no direct experience of material suffering, he does have abstract knowledge of this condition and understands its cause, as we see in his explanation in the Gita of how suffering derives from attachment. Thus his impassibility does not impinge upon his omniscience. However, the abstract knowledge and understanding does not drive his life and provides only a secondary, indirect impetus for his compassion. His life is driven by his love for his devotees, who are either entirely under the same internal çakti that governs his emotional life (in the case of nitya-siddhas) or gradually coming under its influence through their sadhana (in the case of sadhana-siddhas). In other words, Bhagavan is driven by bhakti. (2) Indeed, he is controlled by bhakti. She rules his life, and it is in his relationship with his devotees that his ananda—his love—lies.

Thus the direct impetus for and object of his compassionate glance is his devotees in this world who are pursuing prema-bhakti. He comes to the world out of compassion for them and only indirectly out of compassion for those not yet touched by bhakti. Indeed, it is primarily through the compassion of such devotees that his compassion is passed on to the rest of the world. Such devotees do have direct experience of material suffering, and their resultant compassion for others does not go unanswered by Bhagavan, who lives to please his devotees. Out of love for his devotees, his compassion flows to those whom they feel empathetic toward. His devotees are thus the principal impetus and vehicle for his compassion. In his Gita Bhusana, Baladeva Vidyabhusana comments on how the devotees’ compassion plays out. Such devotees “lament for those who are suffering and think that no one should have to suffer for any reason.” (3) Visvanatha Cakravarti Thakura and Thakura Bhaktivinoda also describe the devotees’ compassion as a secondary quality inherent in their bhakti. (4)

The devotees experience of bhakti differs from that of Bhagavan in that Bhagavan is the object of love and his devotees are the vessel or shelter of love. As such his devotees see everything in relation to Bhagavan and ultimately only Bhagavan everywhere. They see him everywhere and every thing in him. Thus their love extends everywhere, whereas Bhagavan’s love is entirely focused on his devotees. His devotees are the principle manifestation of his krpa-sakti. They are simultaneously one and different from him. Bhagavan is one with the world and one with his devotees, as the energetic is one with its energies, while the two, energy and energetic, simultaneously remain different from one another. Bhagavan is full of compassion, yet it is through the medium of his devotees, who are both one and different with him in an interpenetrating panentheistic sense that his compassion for the world is expressed. (5)

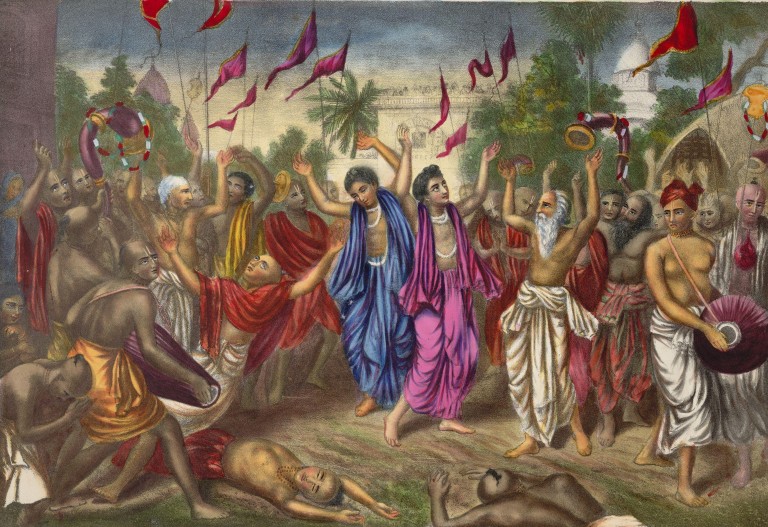

However, in the case of Sri Caitanya we find Bhagavan in the bhava of a bhakta! Thus his devotees have proclaimed him as the most compassionate manifestation of the Godhead. Although he has no direct experience of material suffering, his is nonetheless absorbed in bhakti from the vantage point of his own devotee. He is absorbed in Radha-bhava and Radha is said to be the compassionate nature of Bhagavan. She is the hladhini that bhakti is constituted of, and as such there is a little of Radha in every devotee. Sri Caitanya experiences the fullness of Radha’s love for him from her vantage point and this in turn causes an overflow of the dissemination of bhakti, the indiscriminate blessing that has caused Sri Rupa to refer to him as the compassionate avatara of Kali-yuga—karunaya-avatirnah kalau. (6)

In Sri Caitanya we find both Bhagavan and bhakta, sometimes expressing the bhava of Bhagavan and sometimes the bhava of a bhakta, until he perfectly steps into Radha’s bhava and completes the inner purpose of his descent. With regard to his compassion, the difference in perspective between Bhagavan and bhakta is nicely illustrated in Sri Caitanya-caritamrta when Sri Caitanya glorifies Vasudeva Datta, one of his eternally liberated devotees. At that time, Vasudeva expressed great compassion and requested Sri Caitanya liberate all materially conditioned jîvas in the universe by giving him [Vasudeva] their karma so that they would be free to transcend material existence. While Sri Caitanya deeply appreciated the compassion of Vasudeva, in the mood of Bhagavan he also replied with an air of aloofness to the material condition, teaching that material suffering as a whole has no end and that the liberation of an entire universe was not of much consequence from Krsna’s perspective. (7) In contrast, elsewhere we find Sri Caitanya absorbed in the bhava of a devotee expressing great concern to Haridasa Thakura for the suffering of even trees, plants, and insects. (8)

Sri Caitanya Mahaprabhu has shown by his own example how compassionate love for all animation arising in the context of the culture of uttama-bhakti precedes the attainment of bhakti-rasa. He left his rasa-kirtana in Nadiya to give bhakti to the world, fulfilling the desire of Advaita. He walked the breadth and much of the length of Bharata broadcasting Sri Krsna sankirtana wherever he went. With Advaita’s permission, he entered a life of solitude in his Puri residence, the Gambhira. Thus he taught by his example how to enter his rasa-kirtana of Nadiya. He showed compassion for the suffering animation and administered the medicine of Krsna sankirtana, and in due course this same sankirtana took him inward, where he explored the depths of the ocean of bhakti-rasa. Following his example, showing kindness to all jivas in the context of nama-sankirtana—jive daya krsna-nama sarva-dharma-sara—the sadhaka eventually enters the depths—gambhira—of bhakti-rasa. Thus the sadhaka gradually gains entrance to Gaura’s rasa-kirtana of Nadiya, where his dispensation begins, leading all willing jivas step by step into the courtyard of Srivasa Thakura in eternal nocturnal Nadiya sankirtana.

———

(1) See Bhakti-sandarbha 180 and Paramatma-sandarbha 93.

(2) See Sarartha Darsini 9.4.63–68.

(3) Gita Bhusana 12.13–14

(4) See Visvanatha Cakravarti’s Sarartha Darsini commentary on SB 3.25.21 and chapter 8 of Jaiva Dharma.

(5) Western forms of panentheism stemming from Whitehead’s process theology render God immanent but not transcendent and thus subject to the “process” of life and the experience of material emotions such as empathy along with us. However, in Gaudiya panentheism, God is simultaneously immanent and transcendent and his emotional life is governed by his internal sakti—bhakti—rather than his maya-sakti, from which material emotions derive.

(6) Cc. 1.1.4

(7) Cc. 2.15.160–80

(8) Cc. 3.3.67