by Catherine Ghosh

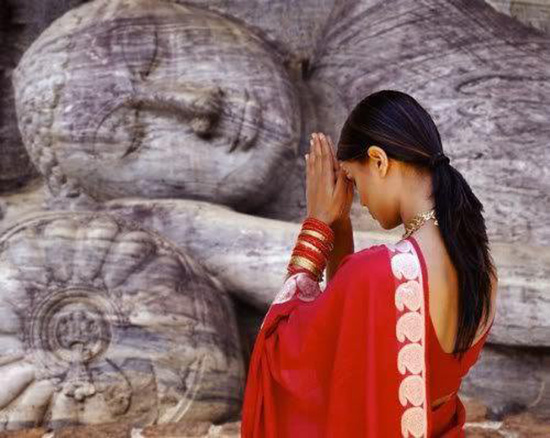

I discovered Buddhist texts the year I turned 14.

I took them with me into the eucalyptus grove across the street from my home, and wondered what it was like for the Buddha under the Bodhi tree. With my eyes closed, sitting in padmasana, I was eager to experience what he had experienced.

The mingling scent of the sea with the eucalyptus leaves fed my meditations: on peace, on the universe, on achieving a harmonious existence within it.

Having been raised by educated liberals who told me I could be whatever I wanted to be when I grew up, as a 14 year old girl I never imagined that my gender could ever be a hindrance on the path toward enlightenment. It wasn’t until five years later, and living as a full-time celibate student in a bhakti yoga ashram, that I became aware of the many prejudices that contemporary women practicing eastern traditions endure today.

From Buddhist texts I wandered into yoga texts, and began to align myself with the bhakti tradition at the age of 16.

Although I had been practicing on my own for three years, it wasn’t until I moved into the ashram that I began experiencing first-hand the way the institutional version of the tradition discriminated against women.

In the ashram we women were not allowed to give classes, we were not allowed to lead kirtans (the call and response chanting), we were not allowed to stand in front of the altar during morning prayers. We were served last during meals, we were last to participate in rituals, we were responsible to pay for our own rent in the ashram while the men had their facilities provided for free and we were not allowed to aspire to become leading teachers or gurus. We lacked a voice in the governing commission of the institution, as those roles were reserved exclusively for the men.

Perhaps worse than all of the restrictions against women were the demeaning and disheartening psychological messages that fueled them, delivered to us on a daily basis, via classes and treatment designed to remind us that our worth as women was only half of what that of the men was.

Like the time I was 20 years old and participating in an urgent temple meeting to resolve a managerial issue that had arisen. There were four of us: three men and myself. The temple president looked around the room and said: “Well, between the 3½ of us we should be able to figure this out!” Though it sounds like something out of medieval India, this event took place in California in the early 90’s, and it sadly wasn’t atypical in such circles.

But is misogyny an intrinsic part of the main tenets of the bhakti philosophy? Absolutely not!

Ironically, the divine feminine, or Goddess Radha, takes priority over anything else in the bhakti tradition, as she is seen as the doorway through which souls unite with the sacred. The verses spoken by Radha and the Gopis in the Bhagavat Purana are at the heart of this ancient tradition, later giving women within the patriarchal, greater Hindu culture more prominent spiritual roles.

In the 12th century, 400 years before the prominent bhakti cult of Caitanya was established, the poet Akka Mahadevi fought for the emancipation of women, ridiculing the accusations against women as “the cause of men’s spiritual fall-downs” and “maya.”

In her own words:

If a woman is a temptation to man, so is man to woman… temptation is thus in the mind of a person, and not in the gender of a person.

Akka Mahadevi was one among 50 female teachers in her day, within her particular bhakti tradition dedicated to educating women to teach religious literature without the typical misogynist misinterpretations.

Much like Akka Mahadevi, women practitioners of bhakti yoga today continue to fight against misinterpretations of the bhakti philosophy that cast unflattering shadows upon them. Though it has been nearly 30 years since the first organized meetings were held in Los Angeles (organized by a dear friend of mine), to counter discrimination against women in the bhakti tradition, the progress has been sluggish. For the women have been up against rigid institutional opposition that continues to exclusively reserve the highest ordinations and teaching positions for men only, prohibiting women from becoming gurus and even participating in certain spiritual practices in some temples.

Much of the opposition appears to be rooted in fear of deviating from what has been written in ancient texts and by previous gurus: both of which contain many derogatory statements about women.

In a desperate effort to preserve the purity of the original bhakti teachings, contemporary male leaders, utterly untrained in theology, allege that allowing women to serve as gurus in the tradition would somehow taint the teachings. The original bhakti paradigm however, at its essence, does not make gender a prerequisite for salvation, liberation or enlightenment.

Much like the women of the bhakti tradition, Buddhist women have faced similar discrimination.

In the earliest of Thervada and Mahayana texts, negative stereotypes of women abound. Influenced by the same patriarchal societies that the ancient bhakti texts were, we find warnings against the temptations of women, who should be cast aside to ensure spiritual progress. Such negative female gender typecasting occurred in both traditions, despite the fact that—at their core—both bhakti and Buddhist philosophies deny gender, race, social status or any other temporary, physical designation as bearing any influence on one’s qualifications to practice and teach spirituality.

The Buddha himself recognized women’s rights to dawn the robes of the Buddhist mendicant, and achieve spiritual enlightenment: something that was previously unheard of in patriarchal Indian society. Unfortunately, after his death, Buddha’s affirmations of a woman’s capacity to achieve liberation also began to die. Particularly as Buddhist literature began to appear, women were carelessly cast as sirens luring men from the spiritual path and thus deprived of many privileges.

Because the psychological conditioning and torture of gender injustice goes deep and has lingering effects that are passed on from generation to generation, it wasn’t until 1987, (well over two millennia since Buddha’s death!), that Buddhist women first began networking globally to counter the damage.

It was the first international conference ever to address the problems faced by Buddhist women. The conference was held in Bodhgaya, India, and H. H. Dalai Lama spoke enthusiastically in the inaugural address of the equal spiritual potential within both men and women, echoing the Buddha’s own sentiments.

Though at the time I was only 17, I would eventually turn to the organizer of the conference—the venerable Bhikshuni Karma Lekshe Tsomo—whose efforts I was deeply inspired by. Having no comparable role model within my own Bhakti tradition, I approached her in the year 2001, after returning from India and Nepal. It was a trip that had inspired me to exercise my voice as a woman in the bhakti tradition, after nearly 15 years of having felt silenced.

Karma Lekshe Tsomo is not only one of the first Buddhist western women to have received full ordination in 1982, and one of the main founders of Sakyadhita International Association of Buddhist Women, but also serves as a specialist in Buddhist studies at the same university in which my father teaches. From the first time I met her 15 years ago, and began familiarizing myself with her revolutionary activism to transform sexist attitudes in Buddhist communities, it gave me hope for the women in the bhakti tradition.

When women are not allowed to give class, to teach, to guide, to serve as leaders, to become gurus and bhikshunis, the entire tradition suffers. By pushing women to the back, Buddhist and bhakti cultures deprive themselves of incalculable assets. And yet, over the centuries most women in these traditions have typically been muted. This has translated into women lacking power: being under represented, unheard, invisible.

This is an unethical imbalance that does each of these ancient, spiritual traditions a great injustice.

It is my belief that when it comes to gender empowerment, women from all traditions form a sisterhood from which we can draw to inspire one another upon our own, individual spiritual journeys. This begins with reestablishing our value within each of our own respective traditions by speaking up. When women’s voices are muted, it is equivalent to telling them that they have no value.

It is an act of violence that ricochets out into society as a whole.

Conversely, when we women feel inspired, supported and encouraged to express our voices, we assert our value, we share our gifts, and we offer the world more of the riches that each of these traditions hold.

Women have an amazing capacity for nurturing and compassion that can transform the world. It begins with ending the silence, emerging from hiding, and exercising confidence in our sisterhood as a whole. I urge you, my dear spiritual sisters, to come out of the shadows and share your beautiful voices with the world. May we increase the visibility of women in the spiritual traditions of the East in a significant capacity, and quit importing misogyny while transplanting them to the West!

Men, after all, don’t have a monopoly on enlightenment.

(If you are a woman who practices Bhakti Yoga and would like to share your voice via poetry, please visit the Vaihsnavi Voices Poetry Project. Just click here to find out how.)

This article was originally published at The Tattooed Buddha.