The English word “holiday” derives from the religious observance of holy days, but today holidays have been extended to include secular days of historical, political, and social significance. Furthermore, whether they are of secular or religious origin, their observance often amounts to more of an escape from one’s day to day routine with little or no remembrance of their original significance.

However, while some may despair at what appears to be an enormous gap between the meaning and the moment that today’s holiday observances often involve, using holidays as an excuse to escape from one’s daily ritual need not be as profane as it sometimes is. After all, yoga also calls for recreation in moderation.

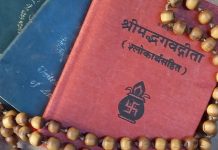

In yoga practice there is a place for play. This we learn from the Bhagavad-gita. In chapter six of this most sacred text, Sri Krishna instructs his student Arjuna in the practices of yoga and meditation. Therein in verse 17 he mentions that a successful yogi knows how to balance his or her practice with recreation (vihara)—to take a holiday.

The central focus of yoga practice involves harnessing the restless mind. The mind is obstinate and difficult to control. The Bhagavad-gita has compared the yogi’s attempt to harness the mind with an effort to capture the wind—not an easy task. However, when the Gita instructs us to factor recreation into the equation of our yogic practice, it suggests that confronting the mind head on is not always the best approach. In order to successfully harness the mind one must learn to work with it rather than against it. One has to allow it some room to roam even as one seeks to bring it under one’s control.

When the mind is not harnessed we are not able to appreciate the value of each and every moment. We are waiting for something to happen without realizing that life—the day to day—is far more meaningful than our restless mind would like us to think. While we are waiting for something to happen, something our mind dictates we must have or do in order to be happy, we are missing the joy of being fully in the present moment and realizing that each moment offers us the opportunity to serve—to give and thereby live life in the fullest sense.

Successfully harnessing the mind thus opens the door to the possibility of making every day a holy day, and such success often involves a well planned holiday from the direct practice of yoga at hand—one that serves ultimately to help us return to our practice with renewed enthusiasm. Indeed, many of the worlds greatest breakthroughs have come not when great thinkers were directly pondering the issue at hand, but rather when they took the time to step back from them, allowing moments of genius to descend, and then on the basis of such inspiration, reapplied themselves to their pursuit.

Thus for one whose life goal is enlightenment in divine love—yogic perfection—there is a place for holidays, both in terms of taking a controlled break from one’s direct practice and in terms of taking a holiday in general. Holidays can be seen as an opportunity to reflect on how one has been spending one’s days, and such reflection can lead to reorienting oneself to take advantage of all that life has to offer—to find the significance and sacredness in each and every day. Such discovery, I believe, is what holy days were originally intended to promote, and when they do so, they themselves can become our most cherished or most holy days—our personal holy days of the heart. In the words of the poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow,

The holiest of all holidays are those

kept by ourselves in silence and apart;

The secret anniversaries of the heart.