Footprints are symbolically important. They represent where we stand, where we go, and what we do. They symbolize what we stand for, stand against, and that on which we stand—our foundation. The symbolism of feet is prevalent in the spiritual circles of the East.

We can also think in terms of our “karmic footprint,” a play on the terms “carbon footprint.” The latter refers to the amount of greenhouse gases that an individual generates in the course of “imprinting” him or herself on the earth. Carbon emissions have been identified as a leading cause of the environmental crisis, and although that finding is beyond reasonable dispute, Eastern spiritual traditions rightly conclude that the environmental crisis is at heart a spiritual crisis—with a spiritual means of resolution.

As animals, we are participants in the natural world. The human animal is nonetheless unique, insofar as it starts to think about and identify itself in ways that less complex forms of life do not. Animals do not philosophize, do not fall in love, and do not experience existential crises. But we as humans undergo a type of crisis upon realizing that nature has a soul—and it is us! Human life is so unique that early Christian thinkers such as Descartes reasoned that humans can be fundamentally distinguished from other animals: “Because I think, I am.” The subjective realm of consciousness is categorically different from the objective world of matter.

Eastern spiritual traditions tend to locate consciousness in the heart, more so than in the head. This is especially true in the bhakti tradition. Modern science may try to understand consciousness by empiric methods—to make consciousness objective such that we can control it and thereby make sense out of it. If consciousness is not something material, however, then everything that we think that we’ve figured out about the world gets turned upside down. Certainly we may have made some progress through science – we have so much medicine and technology and so many new things to point to. But we are not things. That is the teaching from the East.

In fact, there is no methodology in the modern world sufficient to find consciousness. There may be various theories about consciousness that try explain it as something material, but those theories do not even convince contemporaries in the same fields of study. It’s thought that proof of consciousness as immaterial might be unsettling. But truth is always a good thing, unsettling though it may be. In the Eastern view, truth is considered to be beautiful. Being, knowing, and bliss are the elements of consciousness, and these are beautiful things. The East points to the beauty of the inner experience and gives the discipline for knowing ourselves as consciousness. That discipline is called yoga.

Through yoga we can demonstrate that consciousness exists independent of our psychic and physical dimensions. We all want to be; we all want to know; and we all want to enjoy. But in all of this wanting, we may miss the fact that these are our inherent traits. But when we act in terms of our wants, we lose sight of the fact that we are, constitutionally, a unit of eternity, knowledge, and bliss: ananda mayo bhyasat (Vedanta Sutra 1.1.12). Our very source is ananda, joy. Consciousness exists: sat. It is aware of the fact that it exists: cit. It exists for a purpose. What is the purpose? There is no purpose. It is a no-purpose purpose. It is for ananda, only for joy. If you exist only for joy, then in one sense you have no purpose. You have nothing to accomplish. It is only for love, ecstasy.

But in our identification with things, rather than with consciousness, we encounter two dimensions of matter. There is a subtle kind of matter associated with the psychic or mental, and the crude matter of the physical world. The mind is the link between the two. Of course, science does not yet identify mind as distinct from matter, and scientists conflate consciousness with the mind. In Vedanta, however, we distinguish consciousness from mind and mind from matter. Consciousness is categorically different, and mind is different from gross matter by virtue of its subtle form. And for that reason, in the psychic world so many things are possible that are impossible in the physical world. You can have gold and you can have a mountain in the physical world, but you cannot have a mountain made of gold. But in the mind you can have a gold mountain and so many other possibilities. Vedanta identifies the laws that govern the mind, and gives the process, yoga, of distinguishing mind from consciousness.

Yoga seeks to understand and make peaceful that mind that is moving with the waves of emotion: citta-vrtti-nirodha. Yoga is a system for experiencing the theory that there is a difference between consciousness and matter. It means I am not this body, and I’m not this mind, both of which undergo so many troublesome states. To come out from underneath the oppression of the mind and the senses is yoga.

In bhakti, the yoga of love, giving takes precedence. Eventually, what we learn is that by giving things away, we become bigger, we gain. What do we gain? We gain our self because the self has the capacity to give; it’s a lover by nature. That is what we find. When the physical and psychic dimensions of our life close down, life goes on. We must realize that giving, love, is the nature of consciousness, where it thrives. Love must be unmotivated and uninterrupted. If the object of my love is to be interrupted or disappear at some point, I’ve not found the center to which I can give comprehensively and realize the fullness of myself as a unit of consciousness. We call the full center, the most suitable object of love, “Krishna.”

Bhakti yoga is the yoga of the heart. It is a successful experiment in terms of demonstrating this truth to the self. And what could be more important anyway? If you can prove it to yourself, then you should be satisfied. The experiment is not difficult. To sing is not difficult. To chant is not difficult. That’s what we do. We sing about something, usually about love. That’s all. That’s what bhakti yoga is about: honing the love and centering it properly.

The process is simple, but our tendency may be to try to make sense out of everything. Our capacity to reason may set us free from animality, but we are still forced to proceed with caution. A life free of caution is real life. That is the life of the homeland—the heart. The home is within us, and yet we are running everywhere in the other direction for things, trying to make our lives comfortable and to feel at home. The alternative seems so simple, but we’re having a hard time getting home. Thus for this, we need help. This is the idea of a sadhu, of a guru. He’s not a big person, at least not in his or her own estimation. For example, we have a monastery in Central America. There’s an elderly gentleman who used to own the property who is our guide. He knows every fruit, every flower, every tree, every stone, every spring of water, and he knows what will happen in every season. He showed us everything, so we defer to him for knowledge of the local reality. But he just thinks of himself as a common person. To be aware of things is just normal to him. Similarly, to be acquainted with his or her own heart and inner self is ordinary to the guru. This is no big accomplishment in the guru’s estimation. The guru will help you to do the same, to turn you to your own heart, to tell you the things that you should know. “You want to be happy. You are happiness. You want to exist. You are a unit of existence. You want to know. You’re a unit of knowing. Just turn your head this way.”

According to the Vedanta or yoga perspective, we’ve consumed in excess for a long time. We have a huge karmic footprint and we owe accordingly. How do we reduce that karmic debt? This is the idea of the guide. For homegoing, a home-knowing person is essential. Who is the home-knowing person? A home-knowing person is like that lawyer who takes charge of your case when you declare bankruptcy because you have maxed out all of your credit cards and you have no life of your own. Your life is only paying your debts. You declare bankruptcy, and you come under the protection of the court. The lawyer keeps the creditors away. The debt is managed in such a way that you can have a life again. In the same way, our karmic debt is huge: we need some mediation on our behalf. And such simple a thing as turning to your heart can be so difficult. So again, we need some guidance from someone who is not implicated in karma.

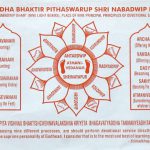

This is the idea of sri guru. He or she also has a footprint: sri guru carana padma. They are called “lotus feet.” A lotus in Indian poetry is the symbol of beauty, but feet are not particularly beautiful. Often they have some cracks, and in ancient times people would readily walk barefoot in the dirt and mud. If you would touch people with your feet, they’d think, “Oh, you touched me with your foot – it’s like you kicked me.” Feet are the bottom of the body, but here they are likened to a beautiful lotus. It means that the guru walks in such a way that he or she is not muddied by the field of matter. The guru does not move in such a way as would implicate him or her in karmic repercussions. Rather, the guru moves – yadrccha—only to give. Contact with such a person is what is considered luck in Vedanta—sadhu sanga, association with saintly persons. Getting it is our good fortune, as there is no reason for it. The guru is moving not out of reason, but out of love, leaving not a footprint of exploitation, but a trail of divine service, that we may follow in the footsteps and find our way home.