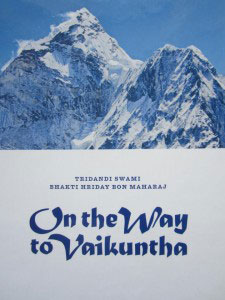

Tridandi Swami Bhakti Hriday Bon Maharaj, On the Way to Vaikuntha. Translation by Dr. Mans Broo (Bhrigupada Dasa). Vrindavan: Radha Govindaji Trust, 2012.

Tridandi Swami Bhakti Hriday Bon Maharaj, On the Way to Vaikuntha. Translation by Dr. Mans Broo (Bhrigupada Dasa). Vrindavan: Radha Govindaji Trust, 2012.

Review by Steven J. Rosen (Satyaraja Dasa)

Tridandi Swami Bhakti Hridaya Bon Maharaja (1901–1982) was a prominent disciple of Srila Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati Thakura (1874–1937), the well-known reformer of Gaudiya Vaishnavism. After Bon Maharaja distinguished himself in the service of the Gaudiya Math, the institution founded by his guru, he was sent to the West as one of Sarasvati Thakura’s most trusted missionaries. In the end, Bon Maharaja’s success was minimal and he returned to India, both to be reprimanded by his guru and to found his own monastery (and educational institution). His story is well known in the Gaudiya Math and in ISKCON as well.

On the Way to Vaikuntha, the book under review here, is an important addition to our knowledge of this consequential religious figure. An English translation of Baikunther Pathe, originally published in 1943, it introduces the reader to a softer side of Bon Maharaja. No longer is he a removed personage who served his guru’s mission but eventually developed blemishes on his reputation. Here he is a soul longing for perfection, trying to compensate for previous offenses, attempting to undo indiscretions of the past.

The book serves to “fill in the blanks,” as it were, showing us Bon Maharaja as a person. So much has been written about him, and his books, disciples, and educational and monastic facilities stand as a testament to his depth of knowledge and his lifetime of devotional endeavor. But here we see another aspect of his person. We see his human side—a sincere soul on a journey to the Ultimate, revealing his character, perceptions, and insights.

Before glorifying salient aspects of this important book, it would perhaps be prudent to express some disconcerting aspects and initial reservations. The translator mentions that this is the first time the work appears in English, and that there is also a Hindi translation as well, but, unless I missed it, we are not informed of the language in which it originally appears. I assume it was Bengali. In addition, there are numerous typos and other careless mistakes—the work would have benefitted from a thorough editing job. Also, I found the peculiar footnote method of this book a bit off-putting: there are no numbers or indicators as to exactly what the footnotes are referring to. The reader only knows that they are referencing an idea found somewhere on the same page, usually directly across from the footnotes themselves.

These problems are minor. There was one reservation that was more fundamental, however, and this involves the very premise of the book: Aspiring to settle in Vrindavana, arguably the holiest of places in the Vaishnava tradition, Bon Maharaja decides that, at this point in his life, he would be unable to remain there, for its spirituality is beyond his ken. He knows that he has made mistakes, taken some missteps, and that he is not worthy of this holy place. Accordingly, he decides to perform austerities by traveling to the Himalayas.

Specifically, he will traverse the Char Dhama (the four holy places), which, he points out, are earthly manifestations of higher spheres of existence: Yamunotri, the source of the Yamuna, is Surya-loka, the planet of the Sungod; Gangotri, where the Ganges originates, is Brahma-loka, where the first created being resides; Kedarnath, high in the Himalayas, is Shiva-loka, the abode of Lord Shiva, greatest among the yogi-devotees; and finally, Badrinath, the penultimate destination, where Vyasa had made his home, is comparable to Vaikuntha, the spiritual realm.

Bon Maharaja reasons that if he could undergo the penances necessary to visit these holy regions, then there will be nothing left for him to see, he will have atoned for his wrong-doings in life, and he could retire to Vrindavana, preparing for death.

At first, this stated premise rubbed me the wrong way. His Divine Grace A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada (1896–1977) spoke disparagingly of journeying to Himalayas merely for purification: “Mayavadi sannyasis engage in meditation or go to the Himalayas, but we have come to Los Angeles. Why? This is our mission.” (Los Angeles lecture, May 14, 1973) Or, “. . . what do you want more? . . . simply by chanting, dancing, and eating prasadam you are making progress. Therefore it is su-sukham. You haven’t got to press your nose and make your head down and starve for three hundred years, nothing like that. Go to the forest, go to the Himalayas. . . . No. At your place you chant, dance, and take prasadam. That’s all.” (Melbourne lecture, April 26, 1976)

And the need to visit “Brahma-loka,” “Shiva-loka,” and so on, is itself suspect. According to the Gaudiya Vaishnava tradition, of which Bon Maharaja is a part, the spiritual master is the sum total of the demigods. Worshiping the guru is thus sufficient, inclusive of all the rest. By such worship, all benefits of spirituality are assured. In fact, the tradition teaches that by engaging in bhakti yoga in this life, one is understood to have performed diverse austerities, including visiting the Himalayas and serving hosts of demigods, in previous lifetimes. Our many lives culminate in Vaishnava seva, which indicates that one has spent numerous incarnations pursuing lesser spiritual goals.

And so the question arises: Why would a Vaishnava find it necessary to undertake such a potentially distracting pilgrimage endeavor? There is a possible reason, and Prabhupada shares this with us, if indirectly, in the Caitanya-caritamrta (Adi 7.157, purport):

The important point in this verse is that Sri Chaitanya Mahaprabhu regularly visited the temple of Visvesvara (Lord Siva) at Varanasi. Vaishnavas generally do not visit a demigod’s temple, but here we see that Sri Chaitanya Mahaprabhu regularly visited the temple of Visvesvara, who was the predominating deity of Varanasi. Generally Mayavadi sannyasis and worshipers of Lord Siva live in Varanasi, but how is it that Chaitanya Mahaprabhu, who took the part of a Vaishnava sannyasi, also visited the Visvesvara temple? The answer is that a Vaishnava does not behave impudently toward the demigods. A Vaishnava gives proper respect to all, although he never accepts a demigod to be as good as the Supreme Personality of Godhead.

This purport helped me appreciate Bon Maharaja’s journey to the Himalayas. In other words, while I initially felt certain reservations about the propriety of a Vaishnava even considering that such a journey was necessary, I came to see, through reading the book and contemplating the above purport, among others, that Bon Maharaja did not make this journey as an ordinary pilgrim. Rather, he traveled as a devotee of Krishna, with respect for the demigods even while distinguishing them from the Supreme Personality of Godhead. His example, as conveyed in this book, is educational and instructive.

Like Narada Muni in Santana Goswami’s classic Brihad-bhagavatamrita, Bon Maharaja undertook his journey not merely with ultimate salvation in mind, but also with a plan to serve Krishna in Vrindavana, thus clearly separating his aspirations from the many “Hindus” who regularly make such pilgrimages.

On the Way to Vaikuntha, then, is a travelogue of transcendental proportions. Bon Maharaja is both poetic and descriptive, a great writer who considers his audience well, elucidating his journey in terms of feelings felt and places visited. The reader, too, will feel a sense of awe when witnessing, through Bon Maharaja’s eyes, the grandeur of the Himalayas, always filtered through Vaishnava philosophy, Puranic stories, and the author’s love for the sacred terrain before him.

But more, the work serves as poignant confessional literature, wherein Bon Maharaja expresses great regret in disappointing Srila Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati Thakura as well as his longing for true spiritual attainment. It is to be highlighted that despite the intense nature of this arduous pilgrimage, Maharaja moves through the various realms as a dedicated Vaishnava, chanting the holy name, honoring prasadam, and living an austere life punctuated by dedication to the Supreme.

Moreover, his affection for his guru is clear. This was a pleasure to read, especially given the negative things that are sometimes said about him in both the Gaudiya Math and ISKCON. The events in this book occurred some six years after Srila Sarasvati Thakura’s demise, and Bon Maharaja had, by that time, been severely castigated not only by the guru himself but by many of his Godbrothers. Still, his dedication is unmitigated, perhaps even enhanced. There are many heart-rending expressions of this. My favorite is the following:

Long years have passed since his disappearance, but I can never forget him. What unprecedented affection! What instructions! What glorification of the secrets of internal worship! What authoritative reprimands! What talks! Since his disappearance, it seems like half a Yuga has passed. Even now, how will I ever find a trace of the moon of Vraja without the compassionate glance of my ever worshipful master Shri Varshabhanavi Dayita Das [Srila Sarasvati Thakur]? Why can I still not just call out ‘Krishna’ in divine madness? What else is there? Why do I still have so much attraction to this despicable life? But oh—there, on the other side of the Ganges, begins the divine land of the gods. Proceeding just a bit further, I shall leave this world behind and enter Svargaloka. Oh gods in heaven! Be merciful to me and let no memory of this world arise in my mind while I dwell in your heavenly land! Hare Krishna, Hare Krishna, Krishna Krishna, Hare Hare, Hare Rama, Hare Rama, Rama Rama, Hare Hare—with these words, I crossed the bridge.

To conclude: In this book, Bon Maharaja shares his dreams with us, both literally and figuratively, and we see a sincere and repentant sadhu. He several times mentions his offenses at the feet of his Master, sometimes with specifics and sometimes more generally, as in the above quote. Whether this is mere humility or reference to his historically verifiable transgressions, it is heartening to read, and I believe he is sincere. Unless one reads the book, it is difficult to tell, and so, for this reason and others too numerous to mention, I highly recommend this gem of devotional literature.

Steven J. Rosen (Satyaraja Dasa) is an initiated disciple of His Divine Grace A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada. He is founding editor of the Journal of Vaishnava Studies and an associate editor of Back to Godhead Magazine. Author of over 30 books on Vaishnavism and related subjects, he lives in the New York area.

For more information: www.waytovaikuntha.weebly.com