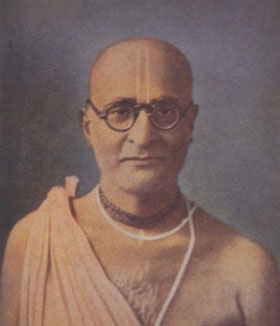

Sometimes, when speaking on the conclusions of bhakti-vedanta, Srila Bhaktisiddhanta Saraswati Thakura Prabhupada is said to have been pounding his fist against the table, raising his voice, and his face would flush red. Once, seeing the color come into his face, Srila Sridhara Maharaja thought to himself, “Now I understand; this is what the sastra means when it speaks of a lotus face.”

Followers of the Gaudiya-Saraswat Sampradaya all over the world have come to know of Srila Bhaktisiddhanta Saraswati as the simha-guru (lion-guru), the naisthiki brahmacari who swore off mangos for his entire life after a small childhood blunder of eating the bhoga of the deity; he who at times practiced caturmasya eating only havisya—unseasoned, unsalted rice and lentils eaten from the ground with hands behind the back; he who fearlessly and relentlessly challenged the distortions of the teachings of Sri Caitanya Mahaprabhu, regardless of the opposition that came. These are but a few of the practices that make us revel in awe of that great soul. What perhaps is not highlighted enough is the fact that all of these things were born out of the tender heart that underpins all the actions of an uttama-bhakta.

Sometimes is a distinction is made between the overtly liberal and accommodating presentation of Srila Bhaktivinoda Thakura and the relatively more rigid methods of his son, Srila Bhaktisiddhanta. Such a distinction is understandable, but it is far from the full story. More than anyone else, Bhaktisiddhanta imbibed the essential teachings of Bhaktivinoda, as well as his desire to see Gaudiya Vaishnavism presented to the rest of the world, and to the intelligent members of society in particular. It was in keeping with these compassionate yearnings that Bhaktisiddhanta stood tall and, as Srila Sridhara Maharaja once put it, “declared totalitarian war on maya.” Bhaktisiddhanta would sometimes say that “to wake up one sleeping soul, to make one conditioned soul aware of his real identity, one should be willing to give gallons of blood.” This was his so-called warfare; he was willing to shed his own blood to serve the opposition; it was not an effort to shed the opposition’s blood in order to conquer it. Sri Caitanya-caritamrta declares, “Bhaye visa jvala haya, bhitare ananda maya, krsna premara adbhuta carita: the wonderful characteristic of love of Krishna is such that although on the outside it may appear unpleasant, internally, one who possesses it is completely filled with spiritual ecstasy.” It was this ecstasy and its natural longing to share itself that filled Bhaktisiddhanta’s heart with compassion and flexibility.

Internal tenderness aside, when we look at the measures that Bhaktisiddhanta actually took in the context of his mission, we can rightly say that in some ways he was even more accommodating than Bhaktivinoda. While Bhaktivinoda made many broad and universal statements in his teachings, Bhaktisiddhanta gave form to his conceptions and in so doing led Gaudiya Vaishnavism into uncharted territory. His had to be a flexibility in practice. This is not to say that Bhaktivinoda’s essential understanding did not translate into his life, it most certainly did, but in formally trying to bring Gaudiya Vaishnavism to the world, Bhaktisiddhanta’s need for adjusting details around essential principles became magnified manifold. The ground-breaking measures he took in service to this truth are more a testament to his powerful character than any forceful mood he displayed while doing it. His tenacity was evident in his printing books and newspapers, engaging with British officials, sending his students to the Western world, erecting marble temples in big cities, dressing his sannyasis in priestly garb complete with leather shoes, and the list goes on. These are the actions of a bhakta unwaveringly rooted in siddhanta and unhesitatingly prepared to bend or break with tradition if he thought such an action could bring people closer to Mahaprabhu, for truly understanding the jewel that is the prema-bhakti marga, how could one be unwilling to stretch in order to share it? Furthermore, the bhakti required to appropriately adjust details of Gaudiya Vaishnavism is many times greater than the bhakti required to maintain the status quo, what to speak of berate others with it, a feat which is more often evidence of undeveloped devotion.

This suppleness is the example we see set by our acaryas, one of constant assessment and reassessment to determine how best to inject bhakti into the environment around them. It is a task which they take on tirelessly, although it is grueling and, in one sense, never met with completion. This is their affection, and those who have had the good fortune of close contact with their guru have seen the palpable nature of this affection on a personal level.

We can see that Prabhupada Bhaktisiddhanta was revolutionary, but just one generation later we find Prabhupada Bhaktivedanta establishing different guidelines that many of his contemporaries saw as a deviation from his own guru. It is undeniable that Srila Prabhupada’s mission was different in many ways, yet his followers know him to be fully surrendered to the vision of the Bhaktivinoda parivara. What then must that vision be? It cannot be one that is bound to a certain style of dress, or specific mannerisms, or the perpetuation of every detail and quirk of a culture that is far from exclusively Vedic in the first place. It cannot even be adherence to what have been termed the “four regulative principles,” for we find differences in those even between Bhaktisiddhanta and Srila Prabhupada and occasions where both of them were willing to break with these mandates. In all of these rules, from those as primary as our diet to those as peripheral as how one ties their sikha, the primary vision was that of enabling jivas to cultivate pure love for Rasaraja Sri Krishna.

As sadhakas and servants of the sankirtan of Mahaprabhu, we must strive to live according to the knowledge that following the guru-parampara means cultivating a compassionate heart filled with devotion unencumbered by ulterior motives. This is the entirety of our path and all else can be seen as relative to this. For most of us, it would be an improvement to simply be able to follow the external guidelines given to us by our predecessors, but nonetheless, we must bear in mind that the extent to which those behaviors constitute bhakti will be determined by the development of a corresponding internal element—something more than mere renunciation, the number of counter-beads moved, or our best calculated attempts to emulate the zeal of the lion-guru. In brief, this “more” is a softening of the heart. Bhakti is the supreme secret in part because it is supremely subtle. It involves merely changing our angle of vision and using our head to soften out heart. Our deepest lessons gleaned from our acaryas’ lives will be those that keep this subtlety in mind and push us to move closer to them in our internal development, not only in the pitch of our roar.