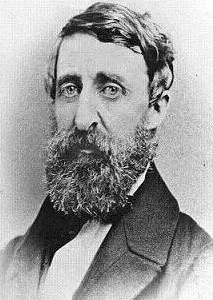

Henry David Thoreau (1817-1862) American Philosopher, Unitarian, social critic, transcendentalist and writer. It was Ralph Waldo Emerson who aroused in him a true enthusiasm for India.

The force from the Upanishads that Thoreau inherited emerged in Walden and inspired not only those who pioneered the British labor movement, but all who read it to this day. Meandering in northeastern Massachusetts, his reverent outer gaze fell upon Walden Pond.

He alluded often to water—the metaphor is clear—the Gita's wisdom teachings are the purifier of the mind: "By a conscious effort of the mind we can stand aloof from actions and their consequences; and all things, good and bad, go by us like a torrent."

He had found his sacred Ganga (Ganges). Living by it and trying to "practice the yoga faithfully" during his two years at Walden, he wrote:

In the morning I bathe my intellect in the stupendous and cosmogonal philosophy of the Bhagavat Geeta, since whose composition years of the gods have elapsed, and in comparison with which our modern world and its literature seem puny and trivial;

and I doubt if that philosophy is not to be referred to a previous state of existence, so remote is its sublimity from our conceptions. I lay down the book and go to my well for water, and lo! there I meet the servant of the Brahmin, priest of Brahma, and Vishnu and Indra, who still sits in his temple on the River Ganga reading the Vedas, or dwells at the root of a tree with his crust and water—jug. I meet his servant come to draw water for his master, and our buckets as it were grate together in the same well. The pure Walden water is mingled with the sacred water of the Ganga (Ganges)."

At Walden he put the Bhagavad Gita to the test, while proving to his generation that "money is not required to buy one necessary for the soul."

(source: The Writings of Henry D. Thoreau – Walden 1989. Princeton Univ. Press. p 298 and How Vedanta Came to the West – By Swami Tathagatananda – swaveda.com).

In the 1840s Thoreau's discovered India, his enthusiasm for Indian philosophy was thus sustained. From 1849-1854, he borrowed a large number of Indian scriptures from the Harvard University Library, and the year 1855 when his English friend Thomas Chilmondeley sent him a gift of 44 Oriental books which contained such titles as the Rig Veda Samhita, and Mandukya Upanishads, the Vishnu Puranas, the Institutes of Manu, the Bhagavad Gita and the Bhagvata Purana etc.

In Indian contemplation he found a "wonderful power of abstraction" and mental powers which were able to withdraw from the concerns of the empirical world to steady the mind and free it from distractions.

"What extracts from the Vedas I have read fall on me like the light of a higher and purer luminary, which describes a loftier course through purer stratum. It rises on me like the full moon after the stars have come out, wading through some far stratum in the sky."

(source: Commentaries on the Vedas, The Upanishads & the Bhagavad Gita – By Sri Chinmoy Aum Publications. 1996. p 26).

"Whenever I have read any part of the Vedas, I have felt that some unearthly and unknown light illuminated me. In the great teaching of the Vedas, there is no touch of sectarianism. It is of all ages, climes and nationalities and is the royal road for the attainment of the Great Knowledge. When I am at it, I feel that I am under the spangled heavens of a summer night."

(source: The Hindu Mind: Fundamentals of Hindu Religion and Philosophy for All Ages – By Bansi Pandit B & V Enterprises 1996. p 307).

"I would say to the readers of the Scriptures, if they wish for a good book, read the Bhagvat-Geeta …. translated by Charles Wilkins. It deserves to be read with reverence even by Yankees…."Besides the Bhagvat-Geeta, our Shakespeare seems sometimes youthfully green… Ex oriente lux may still be the motto of scholars, for the Western world has not yet derived from the East all the light it is destined to derive thence."

In his book Walden, Thoreau contain explicit references to Indian Scriptures such as:

"How much more admirable the Bhagavad Geeta than all the ruins of the East.'

(source: The Writings of Henry D. Thoreau – Walden 1989. Princeton Univ. Press. p 57).

Thoreau described Christianity as "radical" because of its "pure morality" in contrast to Hinduism's "pure intellectuality"

(source: A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers – By Henry David Thoreau p 109 – 111).

"The Vedas contain a sensible account of God." "The veneration in which the Vedas are held is itself a remarkable feat. Their code embraced the whole moral life of the Hindus and in such a case there is no other truth than sincerity. Truth is such by reference to the heart of man within, not to any standard without.

Thoreau, like other Transcendentalist had a breath and catholicity of mind which brought him to the study of religions of India. From the beginning he was disillusioned with organized Christianity (he never went to Church) and like Emerson showed great interest in Hinduism and its philosophy. In comparison to Hebraism, Thoreau found Hinduism superior in many ways. The following passage demonstrates Thoreau’s disenchantment with Hebraism and his love for Hinduism: In 1853 he wrote:

“The Hindus are most serenely and thoughtfully religious than the Hebrews. They have perhaps a purer, more independent and impersonal knowledge of God. Their religious books describes the first inquisitive and contemplative access to God; the Hebrew bible a conscientious return, a grosser and more personal repentance. Repentance is not a free and fair highway to God. A wise man will dispense with repentance. It is shocking and passionate. God prefers that you approach him thoughtful, not penitent, though you are chief of sinners. It is only by forgetting yourself that you draw near to him. The calmness and gentleness with which the Hindu philosophers approach and discourse on forbidden themes is admirable.”

The Christian and Hindu concept of man, Thoreau thinks, are diametrically opposed to each other, the former sees man as a born sinner whereas the latter takes him to be potentially divine. The lofty concept of man embodied in Hinduism appealed to Thoreau. Praising such concept he writes: “In the Hindu scripture the idea of man is quite illimitable and sublime. There is nowhere a loftier conception of his destiny. He is at length lost in Brahma himself ‘the divine male.’

Thoreau – his grand philosophic aloofness, his hatred of materialism, his society, his yogic renunciation and austerity, his lack of ambition, his love of solitude, his excessive love of nature, resulting his refusal to cooperate with a government whose policies he did not approve of, were certain extreme traits like to be misunderstood. Besides, he was a vegetarian, a non-smoker, and a teetotaler. He remained a bachelor, throughout his life, walked hundreds of miles, avoided inns, preferred to sleep by the railroad, never voted and never went to a church, derived spiritual inspiration from the Hindu scriptures like the Bhagavad Gita, and the laws of Manu living an extremely frugal and Spartan life.

The influence of Hinduism made Thoreau a Yogi.

(source: Hindu Scriptures and American Transcendentalists – By Umesh Patri p 98 -240 and India And Her People – By Swami Abhedananda p.235-236).

Henry David Thoreau, was dazzled by Indian spiritual texts, especially the Bhagavad-Gita. He kept a well-thumbed copy of the Gita in his cabin at Walden Pond, and claimed wistfully that “at rare intervals, even I am a yogi.”

(source: Fear of Yoga – By Robert Love – Columbia Journalism Review- December 2006).

"In the Hindu scriptures the idea of man is quite illimitable and sublime. There is nowhere a loftier conception of his destiny. He is at length lost in Brahma himself….there is no grandeur conception of creation anywhere….The very indistinctness of its theogeny implies a sublime truth."

Thoreau's use of Indic scriptures in Walden far outweighs his use of the Bible. He refers to the Bhagawad-Gita, the Harivamsa, the Vedas, the Vishnu Purana, Pilpay (whose fables form the Hitopadesa) and Calidasa. Thoreau annexes India for his own purpose. It is, for example, in the spirit of the Indic myth that Thoreau writes the fantastic passage connecting Walden with the Ganga and Concord with India, and it is in the spirit of India that Thoreau wrote or included the story of the artist of Kuru.

On 6 August 1841 he wrote in his journal that:

"I cannot read a sentence in the book of the Hindus without being elevated as upon the table-land of the Ghauts. It has such a rhythm as the winds of the desert, such a tide as the Ganga (Ganges), and seems as superior to criticism as the Himmaleh Mounts. Even at this late hour, unworn by time with a native and inherent dignity it wears the English dress as indifferently as the Sancrit."

(source: India in the American Mind – By B. G. Gokhale p.22-27).

He even followed a traditional Hindu way of life.

"It was fit that I should live on rice mainly, who loved so well the philosophy of India."

(source: Philosophy of Hinduism – An Introduction – By T. C. Galav Universal Science-Religion. ISBN: 0964237709 p 18).

In his Transcendental thoughts, the world at large conglomerate into one big divine family. He finds beside his Walden pond "the servant of the Brahmin, priest of Brahma and Vishnu and Indra, who still sits in his temple on the Ganga reading the Vedas…" their buckets "grate together in the same well. The pure Walden water is mingled with the sacred water of the Ganga".

Thoreau, the Concord sage, said, "The Vedanta teaches how by 'forsaking religious rites' the votary may obtain purification of mind." And "One sentence of the Gita, is worth the State of Massachusetts many times over".

(source: The Bhagavad Gita: A Scripture for the Future Translation and Commentary – By Sachindra K. Majumdar Asian Humanities Press. 1991. p 5.)

"The reader is nowhere raised into and sustained in a bigger, purer or rarer region of thought than in the Bhagavad-Gita. The Gita's sanity and sublimity have impressed the minds of even soldiers and merchants."

He also admitted that, "The religion and philosophy of the Hebrews are those of a wilder and ruder tribe, wanting the civility and intellectual refinements and subtlety of Vedic culture.

" Thoreau's reading of literature on India and the Vedas was extensive: he took them seriously.

(source: The Secret Teachings of the Vedas. The Eastern Answers to the Mysteries of Life – By Stephen Knapp volume one. p 22).

Like Emerson, the Concord sage, Thoreau, was also deeply imbued with the sublime teachings of Vedanta.

(source: India And Her People – By Swami Abhedananda p.235-236).

He was particularly attracted by the yogic elements in the Manu Smriti. Thoreau embarked on his Walden experiment in the spirit of Indian asceticism. In a letter written to H. G. O Blake in 1849, he remarked:

"Free in this world as the birds in the air, disengaged from every kind of chains, those who have practiced the Yoga gather in Brahmin the certain fruit of their works. Depend upon it, rude and careless as I am, I would fain practice the yoga faithfully. This Yogi, absorbed in contemplation, contributes in his degree to creation; he breathes a divine perfume, he heard wonderful things. Divine forms traverse him without tearing him and he goes, he acts as animating original matter. To some extent, and at rare intervals, even I am a Yogi.

(source: Oriental Enlightenment: The encounter between Asian and Western thought – By J. J. Clarke p. 86-87 and Hindu Scriptures and American Transcendentalists – By Umesh Patri p 98 -240).

Along with Emerson, he published essays on Hindu scriptures in a journal called The Dial.

Thoreau paid ardent homage to the Gita and the philosophy of India in A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers:

"Most books belong to the house and streets only, . . . .But this . . . . addresses what is deepest and most abiding in man. . . . Its truth speaks freshly to our experience. [the sentences of Manu] are a piece with depth and serenity and I am sure they will have a place and significance as long as there is a sky to test them by."