As commonly understood, yoga refers to "union." Some interpret this in terms of body and mind, hoping to become fully integrated people as a result of yoga practice; others see it as a more subtle phenomenon, i.e., a sort of union with the inner self that allows one to integrate body, mind, and soul in a higher spiritual awareness. Ultimately, yoga centers on union with God, though exactly what is meant by "God" is open to discussion.

Bhakti, too, is about union, though it is about uniting with God through love. In other words, for bhakti to exist, there must be "two," the lover and the beloved. This sense of dualism is often forgotten in the modern yoga world, in which lover and beloved are generally merged in some mystical abstraction. In a very real sense, bhakti asks its practitioners to dispense with superficial forms of union.

Further, the word bhakti, while commonly understood as "devotion," or, as Prabhupada translates it, "devotional service," originally comes from the verbal root √bhaj (“to divide, distribute, allot or apportion to”). Think about that: While yoga refers to union, bhakti refers to a diametrically opposed phenomenon: division, separation. As the Monier Williams Sanskrit-English Dictionary tells us, bhakti primarily refers to "distribution, partition, or separation."

Why is that? Because for there to be devotion or love, there must be separation.* This is why "bhaja" has come to mean "worship": If there is division, there are at least "two," and when there are two, worship is possible. A unitary entity does not worship itself, except in extreme cases of narcissism. To quote a famous bhakta, "I don't want to be sugar, I want to taste sugar." Sugar, indeed, cannot taste itself.

Oneness causes relationship to evaporate. We may wax poetic, romantically talking about the oneness of lovers, but, in the end, for lovers to love, they must be two, not one. The so-called "oneness" in this context is merely a feeling of complete harmony, of oneness in purpose, oneness in sensibility. It is a connection (read: yoga) that dissolves all differences. But it is not ontological oneness, and it is the "twoness" that facilitates love.

Thus, while the words bhakti and yoga might mean entirely opposite things, they are aiming for the same goal: closeness or intimacy with God. And not just ordinary closeness, but a closeness so total and all-encompassing that one might call it a kind of oneness.

To attain this exalted spiritual state, practitioners of the conventional eightfold yoga system (Ashtanga-yoga) often think in terms of ascending "the yoga ladder," beginning with pranayama (breathing techniques) and asana (physical postures). Such practices constitute the first two rungs on the ladder, commonly known as Hatha-yoga. This helps one gain mastery over the body, so one can then fix one's mind on single-pointed meditation. After this, the next two rungs are yama ("restraints") and niyama ("observances"), referring to certain rules and regulations that situate one in the mode of goodness. This leads to four higher rungs in which one learns sense withdrawal, concentration, meditation, and samadhi (total absorption in the Supreme).

Ancient yoga texts tell us that the highest rung of the ladder is a merger of bhakti and yoga. This is called Bhakti-yoga, and, when properly performed, it is like an elevator bringing one post haste to the topmost point of the yoga ladder. This is clear from one of the world's oldest and most important yoga texts, the Bhagavad-gita. In fact, the Gita accepts all traditional forms of yoga as legitimate, asserting that they all focus on linking or uniting with the Supreme. Yet the Gita also creates a hierarchy, indicating a yoga ladder of its own: First come study, understanding, and meditation (Dhyana-yoga). These lead to deep contemplation of philosophy (Jnana-yoga) and eventually wisdom that culminates in renunciation (Sannyasa-yoga). Renunciation leads to the proper use of intelligence (Buddhi-yoga) and then proper action (Karma-yoga). And all of this, in the end, leads to Bhakti-yoga.

The Gita's teachings point to a complex inner development, beginning with an understanding of the temporary nature of the material world and how duality affects our everyday life. Realizing that the world of matter will cease to exist and that birth all too quickly leads to death, the aspiring yogi begins to practice external renunciation and gradually internal renunciation, which, ultimately, comprises giving up the desire for the fruits of one’s work (karma-phala-tyaga) and, eventually, performing the work itself as an offering to God (bhagavad-artha-karma). This method of detached action leads to the “perfection of inaction” (naishkarmya-siddhi), or freedom from the bondage of works. One becomes free from such bondage because one learns to work as an “agent” rather than as an “enjoyer”—one learns to work for God, on His behalf. This is the essential teaching of the Gita, and in its pages Krishna takes Arjuna (and each of us) through each step of this yoga process.

Significantly, the Gita’s entire Sixth Chapter takes one beyond conventional yoga, which Arjuna describes as impractical and “too difficult to perform.” Instead, he advises reconnecting with God (Krishna) in Bhakti-yoga, a method described as the culmination of all the rest. According to Krishna, Arjuna is the best of yogis because he has devotion to the Supreme. By the end of this Sixth Chapter, Krishna tells His devotee directly, “Of all yogis, he who always abides in Me with great faith, worshiping Me in transcendental loving service, is most intimately united with Me in yoga and is the highest of all.”

Addendum: Both yoga and bhakti — and indeed Bhakti-yoga — have spread around the world and are now popular among seekers of spiritual science. And yet we now live in Kali-yuga, the age of quarrel and hypocrisy. This means that while various spiritual technologies may spread far and wide, they will be accompanied by misconception and inaccuracy.

Consequently, it is easy to be cheated, and many forms of yoga and bhakti are indeed taught by charlatans or people with an agenda other than spiritual enhancement. The Brahma-vaivarta Puraṇa highlights the degraded condition of people in this age: ataḥ kalau tapo-yoga-vidyā-yajñādikāḥ kriyāḥ sāńgā bhavanti na kṛtāḥ kuśalair api dehibhiḥ "Thus, in the age of Kali, the practices of austerity, yoga, meditation, murti seva, sacrifice and so on, along with their various attendant techniques, are not properly performed, even by the most expert of embodied souls." (This verse is quoted by Srila Jiva Goswami, a 16th-century savant of Bhakti-yoga, in his Bhakti sandarbha, Anuccheda 270.)

The scriptures advise us to avoid such inaccuracy and deception by finding a self-realized teacher in an established lineage of which there are four: the Sri, Brahma, Rudra, and Kumara Sampradayas. These traditions have many offshoot lineages and, with a little study, one can find a bona fide spiritual master. This will allow one to make rapid progress.

In fact, once properly situated, progress comes easily. As it says in the Srimad Bhagavatam (12.3.51), "My dear King, although Kali-yuga is an ocean of faults, there is still one good quality about this age: Simply by chanting kirtan, one can become free from material bondage and be promoted to the transcendental kingdom." And further (12.3.52): "Whatever result was obtained in Satya-yuga by meditation and yoga, in Treta-yuga by performing sacrifices, and in Dvapara-yuga by serving the Lord's lotus feet can be obtained in Kali-yuga simply by Hare Krishna kirtan."

Thus, the central practice of Bhakti-yoga is chanting the holy name of the Lord. The difficulties associated with the yoga process can be set aside in favor of the simplicity of chanting under a master who has realized the holy name. A child can do it. To begin, one need merely open one's mouth and sing with heartfelt sincerity.

__

END

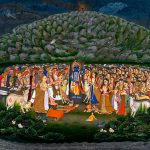

*Indeed, the "origin" of the eternal phenomenon known as bhakti can be seen in the initial "separation" of Radha and Krishna — the Supreme Truth manifesting in two eternal forms, female and male Godhead, respectively. As stated in the Caitanya-caritamrta (Adi 4.56): radha-krishna eka atma, dui deha dhari' anyonye vilase rasa asvadana kari' ("Radha and Krishna are one and the same, but They have assumed two bodies. Thus, they enjoy each other's essence, tasting the exchanges of love.") That is to say, the one Absolute truth divides to enjoy relationship (rasa), which is the highest form of yoga.

Further, in Gaudiya Vaishnava theology, the idea of Vipralambha-bhava or Viraha-bhakti, which is "love in separation," resonates with bhakti as we are defining it in this article: if one is separated from God, one might long for Him, thereby enhancing one's love. For this reason, Viraha-bhakti is considered the zenith of loving exchange with Krishna. It is Viraha-bhakti, in fact, that nourishes Sambhoga, or "union with God," a concept more comparable to yoga as defined in this article. Both are perfect, but in separation there is an intense yearning that is naturally absent in union, making one's love more fully developed.

__

Bio:

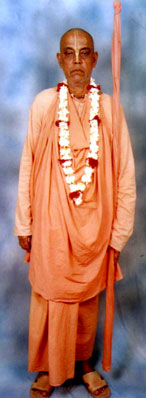

Steven J. Rosen (Satyaraja Dasa) is a disciple of His Divine Grace A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada and author of some 30 books in the fields of philosophy, religion, spirituality, and music. He is associate editor of the ISKCON magazine Back to Godhead as well as founding editor of The Journal of Vaishnava Studies.