Money is flowing like water into prominent government projects on river conservation, but there is little effect on the nation’s lifelines.

In a fantasy India, a cinematic, a fictitious one, the River always flows with serene timelessness. Wherever it goes – icy crags, dusty, thirsty plains or through heavy, damp air – the River contains spiritual depth and emotional weight. All this is lovely to dream, and ideal for tourist brochures where India is called incredible. But to believe that River in India is both a holy and pure is to believe that fiction is fact.

In just over a decade, India’s major rivers have been desecrated. Urban filth and industrial pollution are scientific causes, but what drives them is personal greed and administrative indifference. Environmentalists believe that apart from industrial pollution and sewage, the increase in number of slaughterhouses, dhobi ghats, crematoria and slums are the major sources of pollution in these rivers. Every year, religious idols are immersed in rivers which lose a little more of their life as they are choked yet again. Recently the Supreme Court rejected a PIL filed by a Delhi resident Salek Chand Jain seeking a ban on immersion of idols in rivers and said, “The court can’t ask so many states to impose a ban. You may approach appropriate authorities to have your grievance redressed”. In major towns, as riverbeds run dry with an expanding sheet of silt, the construction business steps in to offer roughly built brick structures that can be ashrams as well as apartment blocks.

Take a Delhi for example. As the host for the 2010 Commonwealth Games, an athlete’s village was built on the Yamuna riverbed by arm-twisting the law and court rulings. This, when Delhi’s sewage mechanism is teetering on the verge collapse. The total sewage generated is 3.470 million liters per day (mld) in a city that has a treatment capacity of around 2.325 mld. What really works in that treatment capacity is only about 1.570 mld due to the inefficiency of the sewage treatment plants and all 11 common effluent treatments plants in Delhi. The required technology is not available, says Chief Minister Sheila Dikshit, “The Yamuna Action Plan I and II have not yielded the desired results despite crores of rupees being spent on them. Though teams were sent to see the Thames and Seine, it would take another seven-eight years for the Yamuna to be like them”. The Yamuna’s violation continues as it moves eastward.

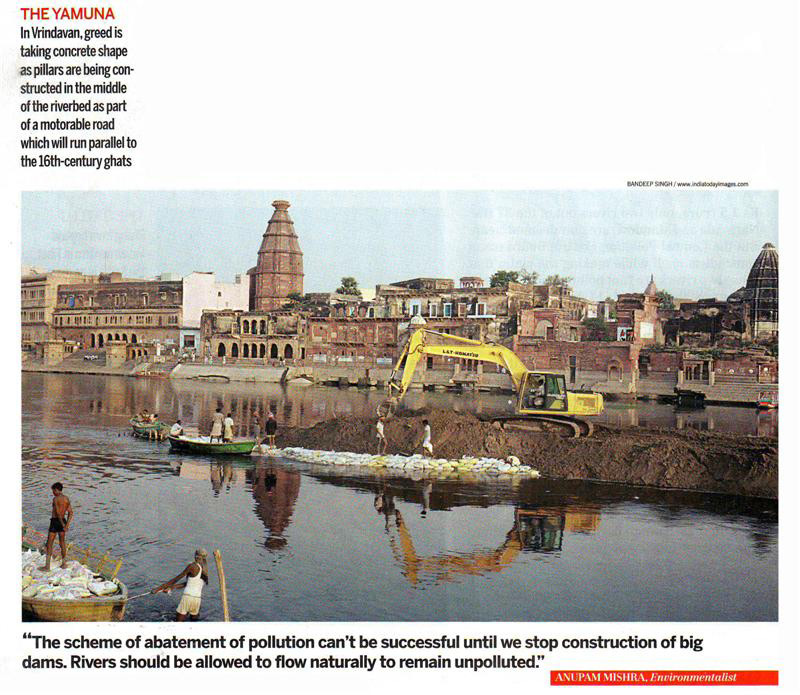

In Mathura, the Yamuna if getting silted as pillars are being constructed by the Mathura-Vrindavan Development Authority in the middle of the riverbed as part of a road which will be parallel to the 16th-century ghats.

Chennai’s four sewage treatment plants take care of 264 mld of sewage instead of the required 530 mld. In Jharkhand, the presence of unregulated mining and mineral industries have silted the Subarnarekha . It is not as if these incidents are the fallout of India Shining. The National River Conservation Plan (NRCP) was launched in 1995 to clean up major rivers. The plan was an expansion of the 1985 Ganga Action Plan, covering 18 grossly polluted river strectches in 10 states at a projected cost of Rs 772 crore. It has now spread to 167 towns in 20 states and includes 38 rivers, including its latest entry, the Panchganga in August 2009.

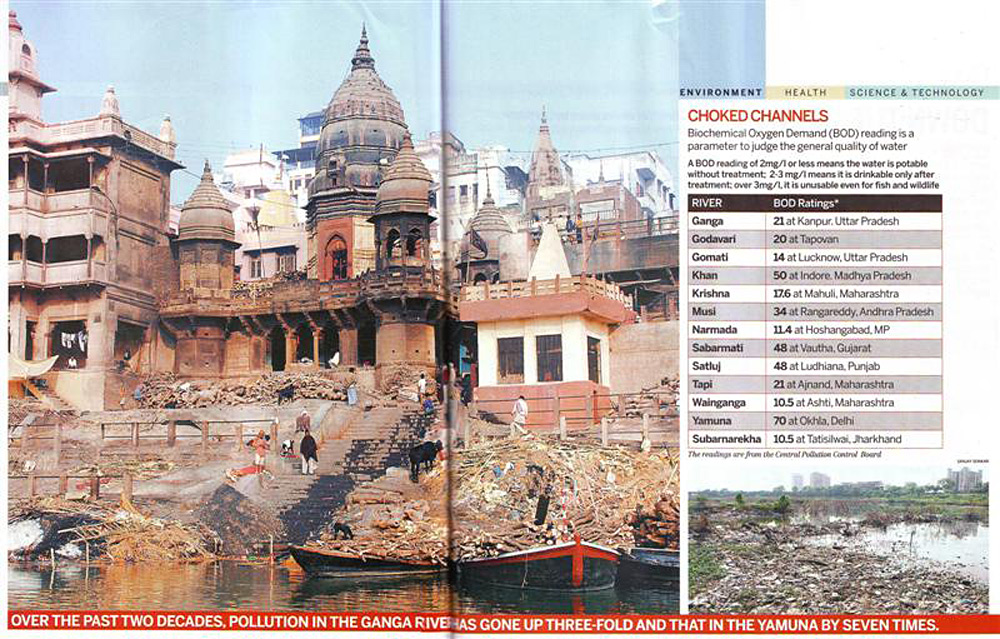

Today, the NRCP is not a focused, successful environmental plan but a bureaucratic abacus whose only job is to add up the moving columns. Officers of NRCP have so far spent over Rs 94.97 lakh on foreign trips to USA, the UK, Israel, the Netherlands, Japan, Austria and Australia to study the pollution control mechanism of these countries. Its programme has cost an enormous Rs 3.892 crore, but the consequences have been a series of failures. Before August of 2009, the NRCP Had to focus on around 2.500 km of 37 rivers. Even as the expenditure for every kilometer of polluted river has risen over Rs 1.5 crore, only two rives out of the 37 (the Narmada and Mandovi) are now deemed clean. But the Central Pollution Control Broad (CPCB) contradicts itself while making the claim that these two rivers are “not polluted now”, as it itself gave the BOD of 11.4 mg/litre for the Narmada at Hoshangabad and 4.7 mg/litre for Madovi at Tonca, Goa.

An INDIA TODAY investigation into the NRCP’s entire misadventure, for which more than 30 applications were filed under the RTI. Act, has revealed its failure as authorities like the CPCB still say our rivers are dirtier than they used to be. Two decades of failure around the Ganga project led Minister of State for Environment and Forests, Jairam Ramesh, to admit in Parliament that the quality of the Ganga and Yamuna is as bad as it was 20 years ago. The reason, he said, was that the pollution load, “has increased much beyond our expectation. The sewage treatment plants have not been running at their full capacity due to the inability of the urban local bodies to provide for full operation and maintenance cost”.

The CPCB’s findings about the NRCP’s rivers state that most of them have BOD (biochemical oxygen demand) readings that are not in the merely polluted range but in that representing severe toxicity (see box). Even though the readings of the CPCB and the CWC are conflicting, experts believe that even in their most poisonous parts, some of India’s most famous rivers are merely urban ditches. What makes the matter worse is the construction of dams on various rivers. Noted environmentalists Anupam Mishra says, “We can’t stop river pollution until we stop constructions of big dams, which was the reason behind the flood in the southern states this year”.

For the rest, time has changed very little, other than the rise in river’s pollution levels. When the GAP I was initiated in 1985, the BOD in the Ganga at Kanpur was 6.9 mg/litre while the latest sample of CPCB marks it at 21. In 1980, the BOD in the Yamuna at Okhla was 10.6 mg/litre, but is now 70. Pollution in the Ganga has gone up three-fold and in the Yamuna by seven times. The NRCP’s files, of course, read perfectly: the programmes include construction of sewage treatments plants, low-cost sanitation works, electric or improved crematoria, river front development and public participation. None of these have been made to work like it should. Every river across India has a sorry story: down south of Chennai, the Cooum and Adayar rivers are famous for industrial pollution. Under the NRCP, Rs 491.52 crore have been sanctioned to clean them while others rivers in the state have been sanctioned Rs 616.17 crore to have particular stretches cleaned. The state’s environment council president L. Antonysamy accuses the Chennai endeavour of lack of accountability: “Chennai Metrowater emphasises that only treated sewage is discharged into the water courses. But it is not happening”.

Kerala’s Pampa, the lifeline of central Kerala and a water source for 30 lakh people, was included in the first phase of the NRCP in 2003-04 and was slated for cleanup by 2008-09. Today, most of the 11 NRCP projects are under construction and work is yet to begin on the largest one. The state Government moved to set up as authority to monitor the slothful work only as late as in August 2008.

The Chambal in Rajasthan has not only suffered from being dirtied but is also the victim of a Centre-state clash over NRCP funding. In 1995, the state asked for Rs 30.53 crore but received only Rs 13.13 crore. A peeved stated Government refused to spend any money on the project. A 2005 request was also turned down, but two years later the state agreed to cough up 30 per cent of a Rs 150 crore project to clean the river. Many projects report have been prepared regularly but there is no certainly when the government will start executing the work. Last week, Punjab Chief Minister Prakash Singh Badal sought immediate release of Rs 302 crore from the Central Government for controlling pollution in the Sutlej and Ghaggar.

Once again, the focus of attention – and the funding – has been the Ganga and our self-obsessed capital’s much – abused Yamuna. In 2007, Prime Minister Manmohan Singh had set up a high – powered committee for conservation and development of the Yamuna and a National Ganga River Basin Authority (NGRBA) in February 2009, being chairman for the both. The first meeting of the NGRBA recently resolved that the Ganga will be pollution-free by 2020 and will cost around Rs 15.000 crore. The World Bank recently agreed to provide an initial assistance of $1 billion for NGRBA in the next four – five years.

No matter how well charted those presentations may be and those funds may sounds, India’s solution to its river pollution does not depend on money. What matters is the integrity of those in the business of implementation and the swiftness and conscientiousness of the NRCP.

(Source: India Today, December 22nd, 2009. Pages 114 – 122)